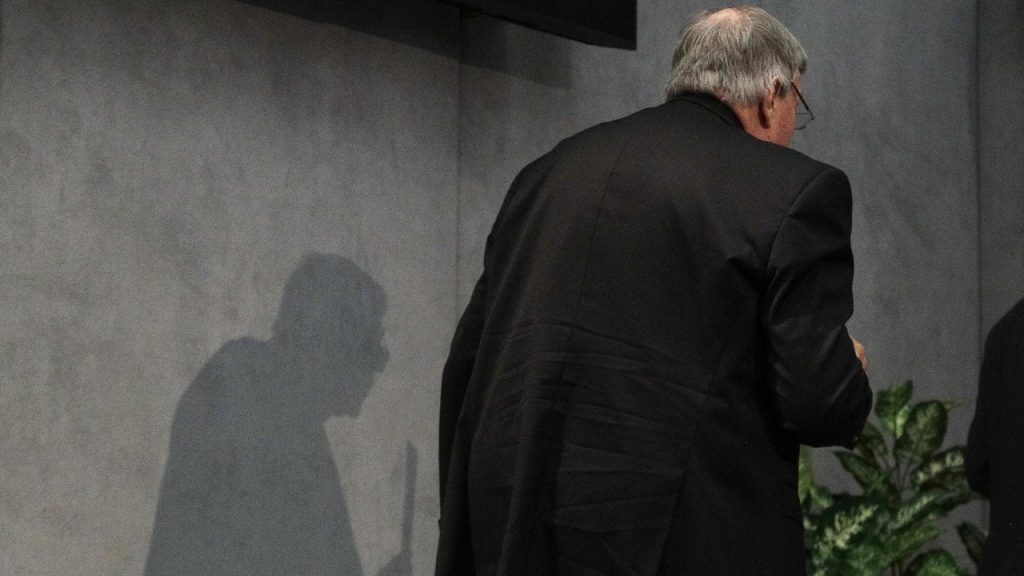

Picture: Gregorio Borgia/AP

Cardinal George Pell has been sentenced to a maximum of six years imprisonment. He will be eligible for parole after serving three years and eight months.

Pell will appeal his conviction. The Court of Appeal has set two days aside in June to consider the Cardinal’s application to appeal his conviction.

The Vatican will wait for the appeals process to conclude before considering Pell’s titles and status within the Church. Similarly, the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse will not release its findings into the conduct of the Cardinal until the appeals process has concluded.

For now, Australia’s most senior Catholic cleric and one of the most powerful men in the Vatican is behind bars, a convicted child sex offender.

Justice Peter Kidd denounced George Pell. Kidd spoke of trust broken and power abused. It is the implicit nature of all child sex offences, the perverse exercise of authority over the vulnerable.

In his sentencing remarks, Justice Kidd referred to “the deluge of publicity” associated with Pell’s conviction.

It is that publicity that bothers me. It is as if all the guilt and shame from institutional child sexual abuse can be conveniently parcelled and packed away with one man.

The grave fear is that we will focus on this story and miss the totality of what has occurred in this country. The fact that the most senior man of one institution has been convicted of child sex offending should not detract from the guilt of other parties or other institutions.

What happened in Australia after World War II was an epidemic of child sex abuse, a crime against our society that is virtually beyond measure. In the wake of the abuse, senior people within institutions — state, religious, secular — committed crimes to cover up the abuse, perversions of the course of justice routinely occurred, culprits were moved on, incriminating documents were destroyed.

Forget the dismal what-aboutery arguments about child sex offending being more prevalent in the home.

While familial child sex abuse occurs in the shadows and reporting is fraught, what we do know is the number and frequency of criminal prosecutions of sexual abuse of children by persons entrusted with their care in institutional settings have no parallel. None.

The nature of the institution may have varied but the behaviour has always been the same.

Victims must be listened to

Principals within institutions reacted instinctively, rushing to protect the reputation of the institution with victims’ rights to justice ignored and with it, their pain amplified.

Victims must be listened to. They must be believed. They must be given the opportunity to attend a police station to make a complaint and know that complaint is subject to investigative rigour by law enforcement.

The Royal Commission examined the story of VicPol detective Denis Ryan who was cast out of the force for attempting to prosecute a paedophile priest in 1972. The Victoria Police Force accepted its corrupt protection of the priest in 2015. Disappointingly, the Commission did not extend its investigations further.

I have reported on credible accounts of corrupt interference in investigations of clerical paedophiles in Victoria up to 1985. Beyond that, retired police officers charged with investigating child sex offences claim they were unsupported by the upper echelons of the Victoria Police Force. Requests to establish strike forces to deal with the burgeoning number of complaints were ignored as late as the mid-1990s.

Victims’ allegations were kicked down the road.

In New South Wales, the Wood Royal Commission found evidence of members of the police force in that state receiving bribes from active paedophiles so they could commit offences against children without consequence. The Child Protection Unit was referred to derisorily by NSW coppers as the ‘Nappy Squad’, its members transferred to it as a form of punishment.

Slow to act

I am certain law enforcement has improved since those unhappy days but is it properly resourced, properly staffed with skilled investigators who will act without fear or favour?

State governments for the most part have been slow to act on the Royal Commission’s recommendations for law reform. The failure to report a child sex offence in most states remains an offence without any serious penalty. In Victoria and Queensland custodial sentences sit on the books but not once has a jail term been handed down. In other jurisdictions those who are convicted of failing to report a child sex offence face only a fine. In New South Wales, it remains an offence but there is no penalty, not even a monetary one.

If we don’t learn from this appalling episode in our social history, we simply cannot ensure that it won’t happen again.

Mumbled expressions of regret uttered in the Royal Commission have been replaced with sanguine, confident voices now that scrutiny has passed.

Just last week, the Catholic Bishop of Armidale, Michael Kennedy instructed Catholic school principals within the diocese not to ask priests for Working With Children Checks. Kennedy has since come forward to clarify his instructions, saying that all priests in the diocese have their WWCCs. But the politics of it were dreadful, not least of all because the Armidale Diocese has a wretched history perhaps as bad as anywhere with the exception of the dioceses of Ballarat and Maitland-Newcastle.

Meanwhile other guilty institutions drag their feet in signing up to the National Redress Scheme.

Less than 100 victims compensated

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse believes there may be as many as 60,000 claimants.

To date, some 3000 applications have been made seeking redress since the body was created in July 2018. Less than a hundred victims have been compensated with the average payment being around $85,000. There is a cap of compensation with a maximum payout of $150,000.

The application form from the National Redress Scheme is a voluminous rat’s maze of psycho-nonsense that has the effect of retraumatising people. It is too long, and asks pointless, intrusive questions. It needs to be dramatically simplified so that the victim is limited to detailing the abuse, when it occurred and where and under which institution or institutions it occurred.

Institutions have been given until 2020 to sign on. People seeking what is at best modest compensation will die waiting for these institutions to sign on. Some already have.

While some institutions have indicated they will sign on, as yet many have failed to do so. These include numerous Catholic orders, a dozen or more Anglican dioceses, the Assemblies of God, Swimming Australia, the Presbyterian Church, The Uniting Church, Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Scouts in four states. The list is shamefully long.

If we cannot get these things right after all that we know now, all the sorrow and pain that has been pushed to the surface, then we will all stand condemned. Worse, we will have ignored the potential risk that this terrible business will happen once again.

This epidemic of child sex abuse cannot be neatly tucked away with the conviction of one man. Pell’s sentencing today is just one step in a much larger process.

This column was first published in The Australian 14 March 2018.

insurers jacking up

https://www.afr.com/real-estate/lacrosse-judgment-widens-cladding-insurance-exposure-for-construction-20190315-h1ceko

“a detailed study from the Australian Energy Market Operator, which looked at why more than 1,190MW of load was shed in three states, why Queensland operated for nearly an hour and a half in an insecure state that could have gone pear-shaped very quickly, and why renewables-dominated South Australia had the most secure grid during the events.””What we do know now is that appears to be able to deliver exactly what the battery boosters say it would – it kept the lights on in South Australia while other states reliant on older fossil fuel technologies suffered wide-spread outages.”

https://reneweconomy.com.au/how-the-tesla-big-battery-kept-the-lights-on-in-south-australia-20393/